Discussed: Richelieu and Cats, or, Displays of Opulence

As many of you know, some of my favourite things are dead people, cats, and ridiculous stuff that happened to aforementioned dead people (and cats). Today we're combining all of this to bring you: dead cat people! My personal favourite historical cat person is Cardinal Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu and Fronsac (more commonly known as Cardinal Richelieu or The Red Eminence).

Richelieu is perhaps best known for his role as antagonist, and occasional ally, in Dumas’ Three Musketeers. The historical man had a phenomenal career as not only a prince of the Catholic Church but also as France’s Foreign Secretary and eventual “First Minister” to the Crown.

In his role as First Minister he sought to modernize and centralize the French state – focusing it around the monarchy and Paris as opposed to more dispersed units of power that had existed previously. He worked tirelessly to balance the powers on the European stage, particularly those of the Habsburgs who controlled both the Spanish and Austrian thrones. To that end he, and France, were heavily involved in the 30 Years War and other disturbances on the continent. For better and worse he supported French exploration and eventual colonization of what is now Canada. Richelieu was also the headmaster of the Collège de Sorbonne and worked to modernize the institution. He was also the founder of various intellectual and academic societies such as the Académie française.

While his reputation has been that of a quasi-villain, the historical personage is obviously more complicated. In the end, Richelieu’s policies eventually led the establishment of France’s absolute monarchy – brought to the fore by Louis XIV – and France’s hegemony on the European stage.

However, the most important thing to all of us is that the Red Eminence was a crazy cat man.

Displays of Wealth and Cats

During his lifetime Richelieu (1585-1642) absolutely leaned into the displays of wealth expected of the upper classes. If you did not live like a nobleman then how could anyone take you seriously?

As Hobbes writes in Leviathan, “For let a man (as most men do,) rate themselves at the highest Value they can; yet their Value is no more than it is esteemed by others.”

This was not a world where one’s worth was determined by one’s love and respect of self but by one’s ancestry and rank. Indeed, part of having self-respect was ensuring others were able to see your standing within society and respecting you and your status accordingly. Therefore, how one displayed wealth in the early modern period demonstrated, in a symbolic manner, how one ought to be treated.

An extant letter from a young Richelieu in Paris: “Since I am a bit glorious, I wouldn’t mind showing off more, but for that I would need a lodging [in Paris] where I could be more at ease. What a pity to be a poor noble.” (Richelieu, Lettres, vol. 1)

One way of ensuring that the respect and homage due to one's rank was preserved and not infringed upon was to implement sartorial laws. These laws dictated what each class and profession was allowed to wear. In Florence, for example, only members of certain ranks were allowed to wear kid-leather gloves. Certain colours and fabrics were relegated to certain classes and professions in order to maintain distinction. Sartorial laws were also a means to segregate those perceived as Other from the rest of the population – this particularly impacted sex workers and lepers.

Another manner of displaying wealth was through patronage and charity. Richelieu was a renowned patron of the arts employing, or displaying artwork of, artists such as Philippe de Champaigne, Simon Vouet, and the architect Jacques Lemercier (who designed and built the Palais Cardinal which has been renamed Palais Royal. It houses part of the French government – I believe the Ministry of Culture and the Conseil d’Etat are there but don’t quote me).

With regards to displays of charity – like the Robber Barons of the United States' Guilded Age and Christmas-Time-Only Charity in modernity – it was both a means of securing one’s salvation as well as a means of self-serving display of rank and wealth.

John Donne on excessive displays of charity:

“In thinks that belong to Action, to Workes, to Charity, there is nothing perfect … there is no worke of ours so good, as that wee can looke for thanks at Gods hands for that worke; no worke, that hath not so much ill mingled with it, as that we need not cry God mercy for that worke. There was so much corruption in the getting, or so much vaine glory in the bestowing, as that no man builds an Hospitall, but his soule lies, though not dead, yet lame in that Hospitall; no man mends a high-way, but he is, though not drowned, yet mired in that way; no man relieves the poore, but he needs reliefe for that reliefe. In all those workes of Charity, the world that hath benefit by them, is bound to confesse and acknowledge a goodnesse, and so call them good workes; but the man that does them, and knows the weaknesses of them, knows they are not good works.” (Donne, Sermons 7, 265)

[NB: Donne was Protestant (though he was raised Catholic) therefore his views on charity are particular to that school of thought. Catholic and Protestant approaches to acts of charity diverge theologically on what it means for your soul and impact on the afterlife. That said, the above still captures the importance that charity was used to show wealth and rank.]

Donne was not against charity, of course, but he cautioned that overly ostentatious displays of it manifested less civic goodness and duty and more aristocratic ceremonies of display.

This shift on excessive displays of wealth, therefore status, via charity and other civic pageantry is a change wrought about in the early modern period (Medievalists correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m pretty sure this is a 16th-17th century shift). And it is one that is more an English phenomenon than French.

Richelieu, throughout his life, very much understood and engaged in opulent displays of wealth which corresponded to his social, political, ecclesiastical and personal identity. Much of this stems from his awareness of the importance of appearance and his previous inability to display himself appropriately: What a pity to be a poor noble.

Informing some of his personal anxiety around wealth was the economic instability experienced by the noble classes due to inflation, warfare, and a bankrupt monarchy. Economic stability and security – and the respectability that came with it – were clear realities in Richelieu’s lifetime. Both in his peers at court but also from his own family’s vacillating fortunes.

Aside from his clothes, which were always immaculate and opulent, his Palais Cardinal is one of the more famous displays of wealth and identity. Richelieu initially purchased l’hôtel de Rambouillet for 90,000 francs in 1624 with the intent to construct a much larger and finer house from it. The planning phase began in 1629, led by Lemercier, and construction commenced in 1633 finishing six years later in 1639. The Palais was equipped with sumptuous apartments, a theatre (Richelieu adored theatre and attended shows regularly), but the crowning glory was the galerie des Hommes Illustres which displayed his exemplary art collection. Included in the gallery were four statues and thirty-eight busts from antiquity and twenty-five portraits (including that of Louis XIII and his own) painted by Philippe de Champaigne and Simon Vouet, among other works.

But do you know what the most important part of the Palais was? The Chatterie.

Yes, dear readers, Richelieu had a room built and dedicated entirely to his cats. There is no way to say: I Am Very Rich than to dedicate a portion of your palace to your cats.

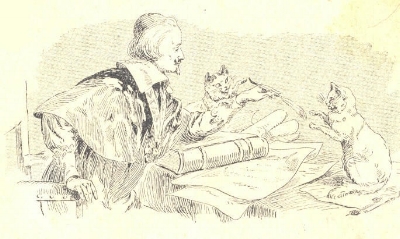

He enjoyed having the animals around like to watch them “gambol about” on his papers. It is a miracle we don’t have extant documents from his tenure with cat paw prints across them. We know that at least in the 1640s he had fourteen cats. That is a goodly amount of cats to own.

Here are some examples of the names Richelieu bestowed upon his beautiful furry friends:

Racan (a famous poet)

Lucifer (just asking for trouble)

Gazette (why, Richelieu?)

Rubis-sur-l’Ongle

Pyrame

Thisbe

Serpolet

Ludovic-le-Cruel

Félimare

Mimi-Piaillon

Ludoviska

Perruque (means “wig”)

Mounard-Le-Fougueux

Gavroche

Soumise

Did he adopt the cats or did they adopt him? Unclear. Irrelevant, really. I’m assuming any time he named his cat something like “Mounard the ferocious” it means they were the sweetest thing on the planet and just wanted cuddles. This is the way of cats.

Sadly we know very little about only a few of his blessed companions. There was a museum in Paris dedicated to Richelieu and his cats but is closed in 2007 which is a loss to the world.

Some Cat Facts:

Rubis sur l'Ongle liked to scratch everything

Pyrame and Thysbe would sleep together with their paws touching, hence why they were named after the famous lovers.

Serpolet enjoyed sunning himself everywhere.

Soumise was Richelieu’s favourite and just wanted cuddles.

Ludovic le Cruel was the resident rat-killer, very important role in rat-infested 17th century Paris.

Ludoviska was rat-catcher's “mistress” which means we all know what Richelieu walked in on one time.

Mounard le Fougueux was a suck for love but simultaneously capricious so he was one of those cats that was like “pet me, pet me, now I attack!”

Upon his death in 1642 Richelieu left the Palais-Cardinal and his art collection to the Crown (the Crown probably would have taken it anyway) but also in his will was money set aside for the safety and well-being of his cats, including the naming of a dedicated cat-care-taker for them.

Richelieu might have run France but that didn’t stop him from loving his cats. Let that be a lesson to us all.