Charivari - Performances of Violence, Justice and Subversion

Charivari - Performances of Violence, Justice and Subversion

I’ve always been fascinated by the use of performance as a means of seeking justice. Whether that be through art, plays, music, or theatre. Western society has always been strongly performative by nature and has only grown more so with new technologies, the internet, the focus on acting out a persona online versus irl (in real life). The initial strong distinction people made between Online and In Real Life was akin to the way you distinguish between an actor on and off stage. However, that line has long since blurred, and for the best, with people coming to understand that Online is In Real Life.

Part of internet culture is the group mentality that comes with it where each corner has a sort of “village” feel to it. No matter which platform you are on you have “your people”. This is very much a natural part of being human but it is fascinating to watch recreations of village or neighbourhood life acted out digitally where one person makes a faux-pas and then the “village” must either correct that person’s course or purge them.

In the early modern period on through the early twentieth century one of the most distinct forms of correcting behaviour was known as the charivari.

Charivari (aka Skimmington Ride, Stang Ride, Rough Music, Shivaree or Chivaree) was a method of maintaining moral and social norms within society. Through public shaming people who acted outside of what had been decreed as “correct” behaviour, such as punishing adultery or other acts of sexual and social deviance, were punished. While a charivari could be used to punish any range of social “sins” it was most usually focused on “incorrect” marriages. This includes adultery, widows marrying again too soon after a husband’s death, a husband or wife who exceeds the social acceptable amount of spousal abuse, or any other form of deviancy.

The nature of the charivari varied depending on where you were. In England, Skimmington Rides, or Stang Rides, were the most common form of this social censure although the rides were performed elsewhere including France and Germany. A Skimmington Ride involved the guilty parties being placed on a donkey or a pole and carried around the town while being beaten with skimmingtons, which are large wooden ladles. Accompanying this would be loud music, people banging on pots and pans, and singing of various cacophonous songs.

A relief from the Great Hall in Montacute House, Sommerset, England portraying a Stang Ride

We have an account of a charivari from Samuel Pepy's Diary date June 10, 1667:

...in the afternoon took boat and down to Greenwich, where I find the stairs full of people, there being a great riding there to-day for a man, the constable of the town, whose wife beat him...

In France, the charvari sometimes took a darker, theatrical turn with the guilty parties being dressed as stags or deer and the villagers, dressed as hounds, would “hunt” them. In some cases animal blood was spilled on the doors of the guilty parties.

There were times when, at the end of the charivari and the guilty had admitted to their crimes, they would be dumped in the local water source as a form of re-baptism back into the community. In other cases it was their effigy that was paraded around and in severe cases, burnt. What was universal was the noise making (hence, “rough music” being one of the names for it), general discord, and deep public humiliation and shame.

What was universal was the spontaneous nature of the charivari and the integral role it played as an act of social cleansing.

Here is an excerpt from the memoirs of Esprit Flechier (1632-1710), quoting an old man who complained about the decay in good conduct of charivari since the days when he used to participate in the them.

…But now all this courtesy [of the charivari] has passed away … All that remains of these old games is a right of exaction, and an imposition of tribute on certain occasions. When a stranger marries a woman from the town, the princes tax him … in order to make him pay for the departure of the nymph whom he carries away. When a widower marries a girl, or a widow a boy, they are taxed according to their condition, for having removed the nymph or young lord who ought to have belonged to some other. These were the only taxes spoken of in past ties. Each enjoyed his goods in peace and owed nothing until his marriage. The imposition was very moderate, a reasonable time was given to pay, and thank God all the taxes were the same! It is true that after a pre-arranged time, people went to collect the sum, and that if payment was delayed a little too long, the custom was that the prince’s officers hurried along to the debtor’s house with a great deal of folly, following their brief, took down the tapestries, disarranged all the furniture, and as was the order of the day, threw everything out of the window. This was done with such good grace that it was an entertainment, and not an act of violence.

Charivaris also had political connotations. When invoked in political situations it was used as a means for those traditionally disenfranchised and with minimal to no access to a political voice to make their sentiments known. Either by acting out on the actual person who warrants their discontent or on an effigy of that person.

These rituals, as violent and shaming as they were, allowed average people of the early modern period to perform a form of justice when they had no access to the justice system. The language of charivari was one of ritual and subversion. It presented an “up-turning” or “inverting” of the world as an act of setting it right again. It was necessary for them to turn the world inside-out, to see the sins of it, to see each other plain, before they could go about setting their lands back in order.

The subversion could be seen in different elements of the public mocking and they ranged from gender swapping, adulterers riding backwards on a donkey or mule (ass backwards), a man being emasculated in some way by his wife, the music being a cacophony instead of pleasant. Charivari is a form of “for the people by the people” justice.

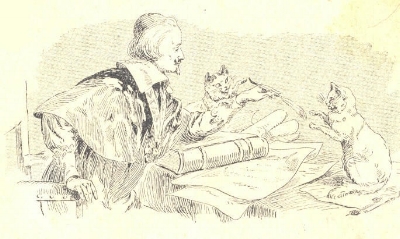

William Hogarth's engraving "Hudibras Encounters the Skimmington"

That said, there were accounts of charivari's going too far resulting in the death of particpants or their accomplaces. Most usually by their own hand due to the shame of it. When living in a small community, a damaged reputation could be drastically life altering. However, as there are few extant records relating to deaths resulting from charivari's, much of what was recorded was hear-say ("I have a friend who knew a guy whose brother killed himself" sort of story). Still, I have no doubt that charivaris resulted in the untimely death of some of the people forced to go through it.

An interesting complication to the charivari as a rural-justice-for-the-powerless view comes to us from Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian Campaign. In 1798 a 29-year-old Bonaparte embarked upon the ill-fated Egyptian campaign and at one point during it ordered a charivari to be performed on Boyer, a French surgeon. Although Boyer was innocent of the charge laid against him, that of cowardice, and ultimately he was not made to perform the following order, this event outlines an interesting attempt to use charivari as state/army imposed punishment.

The order given as follows by Bonaparte:

“(Order.) Citoyen Boyer, surgeon, who has been so cowardly as to refuse help to some wounded because they were supposed to be infected, is unworthy of being a French citizen. He is to be dressed in women’s clothes, and paraded through the streets of Alexandria on a donkey, with a board on his back, on which shall be written: Unworthy of being a French citizen - he fears death. After which he is to be placed in prison, and sent back to France by the first ship.”

This order contains expected elements of a typical charivari: swapped gender roles, riding on a donkey, a parade is made of his humiliation, and the cause of his punishment made clear. In this case, by the placard he must wear as opposed to symbolic images or tokens which were sometimes used. What is interesting is that by having Boyer paraded through the streets of Alexandria Bonaparte not only included French soldiers in the act of public shaming but also extended the performance to Egyptians as well.

Bonaparte, ever the master of propaganda and public displays, had the order printed up in a bulletin and shared publicly. While Boyer was eventually exonerated and not made to perform the charivari, the printed nature of the order meant that not only did all soldiers in Egypt read it but also the general public back in France. This meant that even though Boyer was found to be innocent, the charivari in absentia was still experienced by citizens back home at Boyer’s expense. While this can be seen to be merely a simple act of control and humiliation used to maintain order in a rapidly deteriorating political and military situation, there remains a tension between the bottom-up nature of a traditional charivari and the order given in a military setting.

Indeed, Bonaparte, as General-in-Chief of the Egyptian Army, represented the typical authority figure most often on the receiving end of political charivaris. Or, at the least, his effigy would have been at the receiving end. As one who lived through the French Revolution he would have been familiar with the use of the charivari by the powerless against their oppressors. Therefore, his use of the charivari as a form of authoritative, regimented punishment was an act of inversion. He took a subversive form of justice and “legitimized” it thereby robbing it of its power; making the untamable act of anger and justice tame.

I’ve not found any other recorded instance of Bonaparte using the charivari again as a form of punishment. Perhaps it was deemed too parochial as upon his return from Egypt he was desperately trying to fashion himself as a society Gentleman. He was also deeply committed to distancing himself from anything too “provincial” in an attempt to remove the association of Corsica from his identity. Or, perhaps, it was simply that charivari at the end of the day was an unwieldy weapon of control.

Charivaris continued to be practiced well into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially in the more rural areas of Europe. Photographs taken of the 1902 Corby Pole Fair in England show a man being carried down the street on a pole in the Stang Ride fashion. Indeed, incidents of charivari were recorded as late as 1945 - most usually (and rightfully) performed against Nazi sympathizers.

While the charivari has dissipated in popularity - aided by an increasingly interconnected society, a more accessible justice system to right civil wrongs, and in some places the outlawing of such practices - we still maintain some forms of it. Only, they’ve gone digital.

Movements such as #MeToo can be seen as a form of modern charivari. Unwieldy as any movement is, they are a means for those who have little power to enact some form of justice against those who the system in place protects. To invert the traditional balance of power, even if it is only for a little while. Instead of burning the effigy of the king or church, names become hash-tags. Instead of making an abuser or rapist ride ass-backwards on a donkey while being beaten by their victims, they are publicly shamed in a digital forum.

While the internet making the world increasingly smaller it is no wonder that some form of the charivari has erupted and taken on a similarly global approach. As with the charivari, there are detractors to these wide movements. However, those participating in these social movements would argue, just as those who engaged in charivari would argue, it is sometimes necessary to turn the world inside-out, to see the sins of it, to see each other plain, before you can begin to set things back in order with the aim of creating hopefully a more just and compassionate world than existed before.